Working in a production support role can take you on some wild rides. At times, hunting down the source of a bug can make you want to rip out your hair, and even question your sanity. Quite often though, the harder you work to unravel a problem, the sweeter the satisfaction when you finally get to the bottom of it. This is the story of one of those kind of bugs. While it may have cost me a few hair folicles, the payoff at the end was worth it.

How it all started

I work for a fairly small software development shop. We support a handful of different products, including a desktop app that uses WCF to call back home to one of our services. Out of the blue, we got a report from a user saying they were getting timeout errors in the desktop software related to some functions that called back to our WCF service. Initially, our support team thought this must be a fluke. If our service was down, we would have been flooded with calls. This was just a single desktop, in an office with several installations. Being desktop software, support frequently gets calls from users blaming our software for any and every PC related problem they may have. We hadn’t released any updates to this part of the app for months, so support felt pretty confident that this was not really our problem.

Nonetheless, our company prides itself in customer service, so our support team will try to help as much as they can. They started to look at the usual suspects when network related errors pop up: antivirus, SSL/TLS cert issues, bad internet connection. Nothing obvious turned up. In the mean time, new reports of this same issue started to come in. The numbers were small, maybe 20 of our 10,000 or so installs were having problems. Not enough to make this a critical issue, but enough that we couldn’t write this off as some fluke.

Thats when support called for “the expert”. Unfortunately, our expert in this area was gone. He had moved on to another company several months back. No one else knew much about this particular area of the code in the desktop app, certainly not me. I happened to work on the service this code was calling back to, so naturally, I became the reluctant heir to this problem.

Digging In

I have worked with WCF enough to know she can be a fickle mistress. My first thought was some configuration issue. That led no where. I have also known WCF to bury the real error message, so switched on trace logging. Still not much helpful. The only error in the WCF trace log was:

The request channel timed out while waiting for a reply after 00:00:59.8595997. Increase the timeout value passed

to the call to Request or increase the SendTimeout value on the Binding. The time allotted to this operation may

have been a portion of a longer timeout.

This wasn’t much to go on. There was no reason for this request to be timing out. The vast majority of our clients were able to connect to the service just fine. I trolled through our server side logs, and couldn’t find any evidence that the requests from affected clients were ever making it to our servers. OK, so the the request must be getting dropped somewhere along the way. It is not unheard of for an antivirus or firewall to drop requests like this, so we explored that avenue some more. We went as far as temporarily disabling the antivirus/firewall on one of the affected machines, but to no avail.

I needed more information. We were able to get System.Net trace logs and a Wireshark trace. The System.Net trace showed a different error:

System.Net.Sockets Error: 0 : [1916] Exception in Socket#45648486::Send - An existing connection was forcibly closed by the remote host.

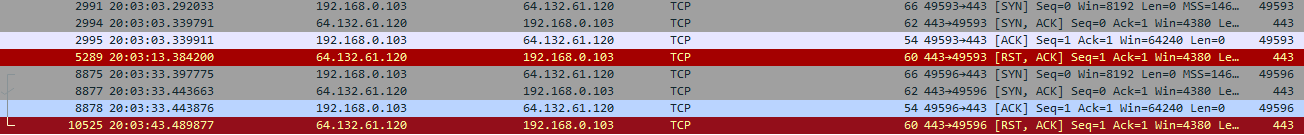

So why was the connection getting reset? The Wireshark trace showed something interesting:

The TCP connection was being opened, then nothing. 10 seconds of nothing. And then the connection was reset by the server. Since the client is connecting over https, you would expect to see the SSL/TLS handshake start immediately after establishing the TCP connection. But here we were seeing nothing.

At this point, I was stumped. I could not explain what I was seeing, and I was starting to feel like I was in over my head. I decided to try and isolate the problem, running a series of smaller tests to get a better idea for where things were going wrong.

Is it plugged in?

I find that when I get stuck on a problem like this, I tend to develop a sort of tunnel vision. I get so focused on one specific symptom of the problem, that I am blind to the bigger picture. I decided to take a step back and do some basic sanity checks.

Can the client browse to the service endpoint in IE? That worked fine. If nothing else, that confirmed that the client could reach our servers, as well as establish a secure https connection, at least sometimes.

So what was different between how our app was connecting to the service and how IE was doing it? I reviewed the connection details in IE and saw that it was using TLS 1.2, while our app was using TLS 1.0. Could this be a SSL/TLS protocol issue? I had seen problems like this before. After the POODLE vulnerablity was published a few years ago, we ran into this kind of problem several times in areas of our apps that communicated with outside vendors. Servers would be updated, dropping support for less secure protocols, sometimes leaving us scrambling to get our end up to date as well.

I really thought I was on to something here. Our app targeted .NET 4.0, which I knew only supported SSL 3.0 and TLS 1.0 by default. Maybe our infrastructure guys did a surprise update to our servers, dropping TLS 1.0? Or maybe these desktops had some fancy new antivirus/firewall that intercepted insecure traffic? I didn’t spend much time asking questions, because I thought I had this case figured out. From my experience following POODLE, I knew that apps targeting .NET 4.0 did not officially support TLS 1.1 or TLS 1.2, but as long as .NET 4.5 was installed on the machine, there is a little trick you can use to get newer protocols working:

ServicePointManager.SecurityProtocol = SecurityProtocolType.Tls | (SecurityProtocolType)768 | (SecurityProtocolType)3072;

The new enum values for TLS 1.1 and TLS 1.2 were added in .NET 4.5, but are not visible to apps targeting .NET 4.0. However since .NET 4.5 is an inplace update to the .NET framework, as long as .NET 4.5 is installed on the machine, this little hack will work. I put a release together with this change, and got it out to one of our broken clients to test, feeling confident I was about to be a hero.

I was quickly disappointed. This change made no difference. I was stubborn though, and desperate. I couldn’t give up on this line of thinking, partly because I couldn’t come up with any other plausible explanations for why these clients were having issues.

A Controlled Experiment

The next question I wanted to answer was, could these clients make a WCF call to our service using any SSL/TLS protocol? I decided to put together a test app to gather information in a more controlled way. I wrote a little .NET 4.6 console app that attempted a series of WCF calls, switching from SSL 3.0, to TLS 1.0, to TLS 1.1, to TLS 1.2.

As I was putting together this test app, I started to develop another theory. Our WCF service was configured to use msbin for the message encoding. Maybe these clients had a firewall that was doing deep packet inspection (DPI), and was dropping these packets because of the binary data? I decided to test that theory out as well. I exposed a plain XML endpoint for our service, and added a second series of calls to the test app that went to this new XML endpoint, again cycling through all the different SSL/TLS protocols.

We got a chance to try this test app out on one of the affected machines, and lo and behold! None of the calls worked… I can’t say that I wasn’t disappointed with the result, but it did prove a few things in my mind. This was not a problem with something specific to our desktop app. I had just built an entirely new app, fresh source code, and it too was experiencing the same issues. Also, I was now convinced that this had nothing to do with the SSL/TLS protocol being used, and it seemed very unlikely that this was a antivirus/firewall issue.

A More Improbable Explanation

I was ruling out some possible explanations, but I didn’t feel like I was getting closer to finding what was actually going wrong. Reviewing all the information I had gathered up to this point, my test in the browser proved that these machines could access our service, while the Wireshark trace showed that the SSL/TLS handshake was not starting, though my test app suggested that this was not an issue related to any specific SSL/TLS protocol.

Something must have changed on these systems. They were working fine one day, and stopped working the next. I knew it wasn’t our code that changed. I decided to start looking for other things that may have changed. Two areas sprang to mind in particular. First, had any other software been installed recently on these machines? I could imagine a scenario where some 3rd party app came in, mucked with the registry, and started breaking things. The other thing that came to mind was a problematic Windows patch. Even Microsoft makes mistakes when building software (can you believe that?), so it is not unheard of for a patch to cause unexpected issues.

There is a command you can use to get a list of hotfixes applied to a machine:

wmic qfe list full

I asked our support team to start gathering this data anytime they got a report of the issue. This allowed me to address two questions. Could we identify a patch common to all of these affected machines? And which patches were installed around the the time the machine started having issues? On the first machine we got this information from, I found one patch in the list that jumped off the page, KB4014504. While this patch said it was for .NET 3.5, everything else about it seemed suspect. Microsoft’s description of the patch was:

This security update for the Microsoft .NET Framework resolves a security feature bypass vulnerability in which the .NET Framework (and the .NET Core) components do not completely validate certificates.

So the patch was directly related to SSL/TLS, and it had been installed on this machine the same day they started seeing issues. Digging into the details of the patch a little deeper, with this change .NET would start validating the EKU extension of a certificate. I had never heard of this extension before, so I quickly read through the proposal and tried to verify that our cert had been issued properly. I also passed this along to our infrustructure team, and they assurred me that everything was in order with our cert.

I was still skeptical, the circumstances surrounding this patch seemed incredibly suspect. The KB mentioned a couple of workarounds you could implement in case any of your certs had issues with their EKU extensions, presumably to buy some time for you to get things straightened out. I had our support team try all of the work arounds listed. No dice. I even had them try and uninstall the patch. Still didn’t fix the issue.

Process of Elimination

I found myself getting more an more desperate, grasping at straws, willing to try anything. IE could connect to our service no problem, WCF could not. Could the problem be with WCF? I decided to try and remove WCF from the call stack altogether. I hacked together some code to call our service using the TcpClient and SslStream classes.

using (var tcpClient = new TcpClient("our.domain.name", 443))

using (var sslStream = new SslStream(tcpClient.GetStream()))

{

sslStream.AuthenticateAsClient("our.domain.name");

var request = // used fiddler to capture the raw request to the service from my machine, which was working fine

sslStream.Write(request);

}

We tried this out on one of the affected machines, and again it didn’t work. So whatever the issue was, it was beneath the WCF stack. The call to AuthenticateAsClient was taking 30 seconds. This lined up with what we were seeing in the WireShark trace. The TCP connection was opened successfully, but the SSL/TLS handshake was getting hung up. Something was going wrong in that AuthenticateAsClient call. I started to look for alternative SSL/TLS implementations for .NET, thinking this could be a bug somewhere in the BCL. This led me to the Bouncy Castle library. I updated the test app I had written, adding some code to attempt calling our service using the Bouncy Castle APIs. There were a couple of hoops to jump through. I needed to provide an implementation for the DefaultTlsClient and TlsAuthentication classes, but it wasn’t too painful:

public class MyTlsClient : DefaultTlsClient

{

public override TlsAuthentication GetAuthentication()

{

return new MyTlsAuthentication();

}

public override int[] GetCipherSuites()

{

return base.GetCipherSuites();

}

}

public class MyTlsAuthentication : TlsAuthentication

{

public TlsCredentials GetClientCredentials(CertificateRequest certificateRequest)

{

return null;

}

public void NotifyServerCertificate(Certificate serverCertificate)

{

// don't care

}

}

With that out of the way, I could attempt the service call as follows:

using (var tcpClient = new TcpClient("our.domain.name", 443))

{

var handler = new TlsClientProtocol(tcpClient.GetStream(), SecureRandom.GetInstance("SHA1PRNG"));

handler.Connect(new MyTlsClient());

var request = // used same fiddler capture as before

handler.Stream.Write(request);

}

We tested this out on one of the affected machines, and it worked! I was somehow excited, confused, and worried all at once with this result. I was excited that I had gotten the call to work, and it all but proved that this bug was not with our code. Confused because I still couldn’t explain why this worked, and the SslStream version didn’t. Worried wondering how we would be able to fix this, since the bug was not in our code.

Besides, our clients did not really care if the bug was in our code, or .NET, or Windows, they just wanted to be able to use the software they were paying for. So, while I felt like I had made some progress, I still had more work to do. I needed to find what was causing this problem.

Read the Source

Once upon a time, there lived an evil king who ruled upon a throne of prioprietary software and anti-competitive practices…

That was a long time ago though. The king has since left (off trying to rid the world of malaria and what not), and the kingdom he left behind has transformed into something few people could have imagined.

Microsoft ♥ Open Source.

For real, you can go browse the full source code to the .NET Framework right now.

I had a good idea where my problem was, the AuthenticateAsClient method, so I looked up the implementation for that method and starting walking through the code. Nothing really jumped out at me. I saw some initialization code around standing up a SecureChannel instance. I was starting to make some connections though between what I had seen in the System.Net trace logs, and what I was seeing in the source code. Here are 2 consecutive log entries from System.Net trace log:

System.Net Information: 0 : [4436] ConnectStream#21800467 - Sending headers

{

Content-Type: application/soap+msbin1

Host: our.domain.name

Content-Length: 805

Expect: 100-continue

Accept-Encoding: gzip, deflate

Connection: Keep-Alive

}.

ProcessId=3020

DateTime=2017-06-05T21:43:54.3987861Z

System.Net Information: 0 : [4436] SecureChannel#61986480::.ctor(hostname=fulfillment.creditinfonet.com, #clientCertificates=0, encryptionPolicy=RequireEncryption)

ProcessId=3020

DateTime=2017-06-05T21:44:24.4028294Z

Notice that 30 seconds pass between opening the stream, and when the SecureChannel constructor is invoked. From the source code, I could see that log line is the first line in the body of the constructor. This must mean the issue is occurring somewhere between the start of the AuthenticateAsClient method, and when the SecureChannel constructor was being invoked, right? I certainly thought so. I spent far more time that I would like to admit scrutinizing every single one of those 45 or so lines of code. I just couldn’t find anything to explain where the 30 seconds was being spent.

Digging Deeper

I was starting to wonder, what if this is not a .NET problem? What if it goes deeper than that? Could there be a problem with some system call that .NET was making? It seemed very unlikely, but I didn’t know what else to look for. I found an awesome tool called API Monitor that logs Windows API calls that your application makes. We once again got on one of these client’s machines (this was getting embarassing at this point) so that we could grab an API Monitor trace while the test app I had written was running. API Monitor collects a lot of data. It took me some time to dig through all of it. I started off by correlating timestamps between the System.Net trace log, and the API Monitor trace, trying to hone in on any system calls being made during the long pause I was seeing. Unfortunately, there were thousands of calls logged during that time, too many for me to make sense of. I then started playing around with the filters in API Monitor, eventually arriving at a filter to only show calls taking more than 1 second:

I had found a smoking gun! One system call was consistently taking ~15 seconds to complete, CryptFindOIDInfo. I reviewed the docs for this API to get a better idea about what it was used for. The docs include one very important remark:

The CryptFindOIDInfo function performs a lookup in the active directory to retrieve the friendly names of OIDs under the following conditions:

- The key type in the dwKeyType parameter is set to CRYPT_OID_INFO_OID_KEY or CRYPT_OID_INFO_NAME_KEY.

- No group identifier is specified in the dwGroupId parameter or the GroupID refers to EKU OIDs, policy OIDs or template OIDs.

Putting together the pieces

OK, so I knew exactly which system call was causing the delay, CryptFindOIDInfo, and I had a good idea why it could take awhile, since it may do a lookup against the domain controller. This also helped to explain why we were seeing such a small number of users reporting this issue, the vast majority of our client’s machine’s were not part of a domain. The big open question was, why did this start happening out of the blue?

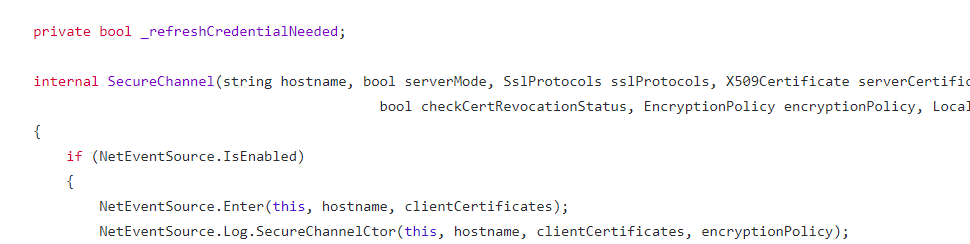

I went back to the .NET source code to try and find my answer. I wanted to find where this CryptFindOIDInfo call was being made. This turned out to be easier said than done. I found 7 different extern definitions for the CryptFindOIDInfo method in the source code. I had to review the call hierarchy for all of these to try and work my way back to the SslStream code. I finally found my way back to here:

private readonly Oid m_ServerAuthOid = new Oid("1.3.6.1.5.5.7.3.1");

private readonly Oid m_ClientAuthOid = new Oid("1.3.6.1.5.5.7.3.2");

internal SecureChannel(string hostname, bool serverMode, SchProtocols protocolFlags, X509Certificate serverCertificate, X509CertificateCollection clientCertificates, bool remoteCertRequired, bool checkCertName,

bool checkCertRevocationStatus, EncryptionPolicy encryptionPolicy, LocalCertSelectionCallback certSelectionDelegate)

{

GlobalLog.Enter("SecureChannel#" + ValidationHelper.HashString(this) + "::.ctor", "hostname:" + hostname + " #clientCertificates=" + ((clientCertificates == null) ? "0" : clientCertificates.Count.ToString(NumberFormatInfo.InvariantInfo)));

...

}

I had been here before. It took a while for it to sink in. Remember these trace logs?

System.Net Information: 0 : [4436] ConnectStream#21800467 - Sending headers

{

Content-Type: application/soap+msbin1

Host: our.domain.name

Content-Length: 805

Expect: 100-continue

Accept-Encoding: gzip, deflate

Connection: Keep-Alive

}.

ProcessId=3020

DateTime=2017-06-05T21:43:54.3987861Z

System.Net Information: 0 : [4436] SecureChannel#61986480::.ctor(hostname=fulfillment.creditinfonet.com, #clientCertificates=0, encryptionPolicy=RequireEncryption)

ProcessId=3020

DateTime=2017-06-05T21:44:24.4028294Z

I had assumed that since the long pause came before the SecureChannel# log line, the issue was occurring prior to the SecureChannel constructor being invoked. The devil is always in the details. In C#, instance fields are initialized before the contructor body executes. In this case, m_ServerAuthOid and m_ClientAuthOid were being intialized, triggering the call to CryptFindOIDInfo. On clients with a misconfigured domain controller, this call was timing out, leading to a slow yet emphatic boom in our app. Hallelujah! I finally had a solid explanation for what was going on!

So why was this just now becoming an issue? Well, remember that patch from before, KB4014504? These OIDs being initialized were the OIDs for the Client Authentication and the Service Authentication usages of the EKU extension. This issue had to be related to that patch. But, I had already tried uninstalling the patch from one of the affected machines, and it didn’t fix the issue. So what gives?

Turns out the process for patching .NET is a bit complex. There are really several different versions of .NET being maintained concurrently (3.5, 4.5.2, 4.6, 4.6.1, 4.6.2, Core, etc). Whenever a security vulnerabilty is discovered, a patch has to be released for all supported versions of .NET that are impacted. So a particular vulnerability may be addressed by a half dozen different patches, each targeting different versions of Windows/.NET. I eventually found my way to the security bulletin Microsoft had published for this vulnerability. That was the final piece of the puzzle I needed to start addressing this issue.

Success! Kind of…

So I finally had a solid explanation for what was going on here. Microsoft had released a security patch that required a couple OID lookups. These lookups would execute against the domain controller when the machine was part of a domain, which sometimes could take a long time complete, preventing SSL/TLS connections from being established.

I also had a potential workaround: remove the KB identified in the security bulletin from Microsoft for the Windows/.NET version installed on the client’s machine. Before attempting this on a client’s machine, I wanted to verify this would work as expected on my own machine. I figured I could decompile the System.dll I had installed before and after removing the patch. If I could see the OID lookups go away, I could feel confident this would fix our issue.

Windows does not make it easy to get to the .NET assemblies installed on your machine. You can find them at C:\Windows\assembly, but Windows will by default give you a special view of this directory, preventing you from seeing the actual files. One way around this is to map a drive to this folder. This will prevent Windows from hiding the real file system structure from you.

SUBST Z: C:\Windows\assembly

Now I could get to my System.dll at Z:\NativeImages_v4.0.30319_64\System and decompile it. Here is the SecureChannel class before uninstalling the patch:

And here is the same section of code after uninstalling the patch:

That was all I needed to see. I armed our support team with the security bulletin, and had them start reaching out to customers that had been having issues to try uninstalling the troublesome patch. It wasn’t long before we got confirmation that this did in fact fix the issues the clients were seeing, and I could finally breath a sigh of relief.

A happy ending, almost

That sigh of relief was oh so satisfying, but short lived. There was a big BUT with this workaround. We were getting ourseleves into the business of uninstalling security patches from client machines. Not ideal. Further, any future patches to the same DLL would also include this fix. And even more problematic, .NET 4.7 had just shipped with this change included, so there is no patch to uninstall. You have to go back to a previous version of .NET. I needed to come up with a more permanent solution.

Open Source FTW

Remember when I said Microsoft ♥ open source. I really meant it. Not only is all of the source code for .NET available, but for .NET core, the entire development process runs through GitHub. Issues, pull requests, everything. Little did I know how deeply Microsoft had really bought into this movement.

I knew I would need to get Microsoft involved to get this fixed, so I had started by opening an issue on the connect website. That didn’t get me anywhere. My employer provides MSDN subscriptions for all developers, and it turns out that you get a couple of free support cases included with that, so I went ahead and opened a ticket through that channel as well. In the mean time, since I knew the exact line of code where this problem was introduced, I went ahead and submitted a pull request to the dotnet/corefx repo on GitHub.

To my suprise, within a couple of hours, one of the core contributors to the corefx repo had reviewed my pull request and replied! I was stunned. A few people got involved to review the case, suggested changes, and over the course of a few days, the PR was accepted.

To be fair, the MSDN support was very good as well. A support rep did reach out to me and stayed in contact all the way through until the official fix was released.

So, after all that, I had found the bug, discovered a workaround, and even helped with contributing a fix. It had been a long and difficult road, but along the way I had learned quite a bit, and can even now call my self a contributor to the .NET framework. Not too shabby.